The call came in from a plant supervisor after a minor chemical splash incident. No one was severely hurt, but the follow-up report told a bigger story: unlabeled secondary containers, dusty Safety Data Sheets, and a crew that “knew the colors on the label” but could not explain what any hazard statements meant. The supervisor was frustrated. He thought his team had already “done the training.”

That supervisor is not alone. Many leaders enroll participants in a one-time class, hoping it addresses their responsibilities under the GHS and the Hazard Communication Standard.

A well-designed Intro to GHS and HazCom Safety Training program, supported by clear supervisor follow-through, turns regulations into routines.

This guide outlines the key takeaways supervisors should apply from any GHS hazard communication basics course and in the field, shift after shift.

Why Hazard Communication Basics Matter For Supervisors

Chemical hazards rarely show up as dramatic scenes. More often, they present as slow headaches in a paint booth, mild rashes after cleaning a tank, or burning eyes during a hurried line change. Supervisors stand between everyday tasks and long-term health outcomes.

Hazard communication training gives leaders a shared language with their crews. Signal words, pictograms, and hazard statements are not merely paperwork; they are concise, powerful messages that prompt workers to pause before they pour, mix, or clean.

When supervisors use these concepts in daily conversations, employees stop seeing labels and Safety Data Sheets as “office documents” and begin to see them as tools.

This is also where legal responsibility lives. Supervisors are often the ones assigning jobs, approving products on the floor, and responding first when something goes wrong. Strong knowledge of hazard communication fundamentals gives them confidence in those moments rather than relying on guesswork.

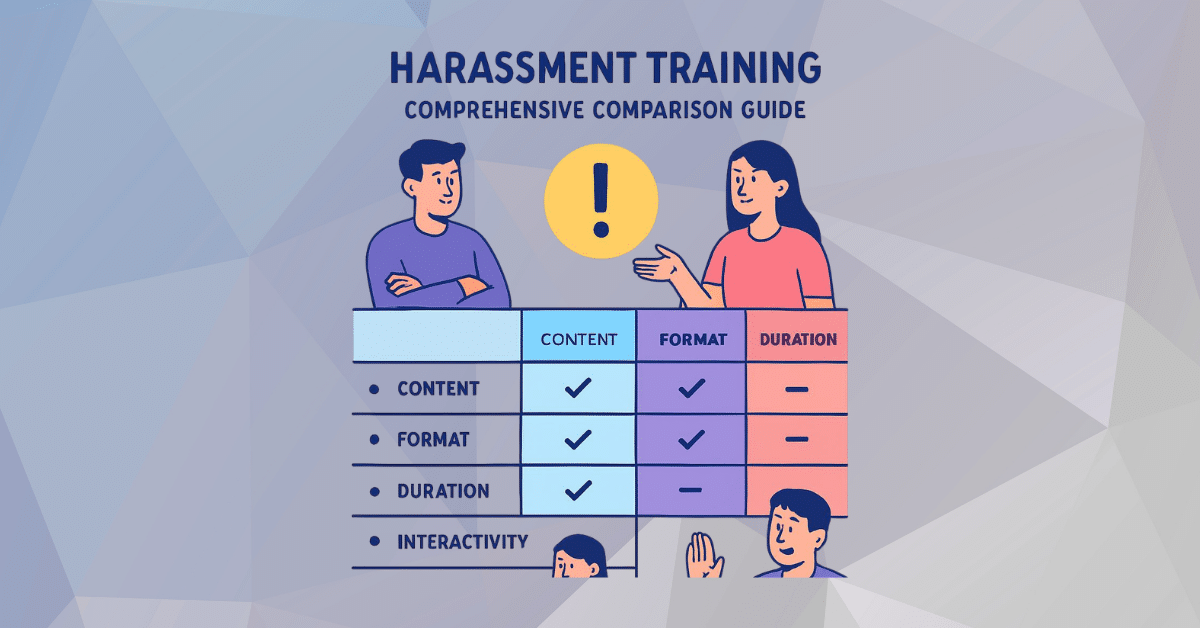

Labels, Pictograms, And Signal Words Your Team Must Recognize

Every container is a conversation with your crew. GHS labels convey information that workers can read in seconds, provided supervisors routinely draw attention to them.

Key label elements include the product identifier, supplier information, signal word, pictograms, hazard statements, precautionary statements, and any supplemental information. Supervisors should be comfortable walking a new hire through each part, using real containers from their own workplace.

Signal words such as “Danger” and “Warning” are designed to elicit different levels of caution. Pictograms immediately indicate whether a product may harm the lungs, eyes, skin, or the environment.

During a shift start meeting, a supervisor might hold up a container and ask, “What are the hazards here?” and “What are the precautions?” Over time, labels stop being background clutter and become an active part of how the team discusses risk.

Safety Data Sheets That People Actually Read

Many workplaces have a thick SDS binder sitting in a corner or an icon on a shared tablet that no one opens unless required. Supervisors can change that pattern through simple habits.

An introductory course should demonstrate to leaders how SDS sections are organized, particularly those covering hazards, safe handling, PPE, storage, and emergency measures.

Instead of expecting workers to memorize section numbers, train them to look for the questions that matter: “What can this chemical do to me?” “How do I store it?” “What happens if it spills?” “What do we do if someone is exposed?”

Supervisors can build SDS use into pre-job planning. Before a new task that uses a chemical, take three minutes to open the SDS and answer one or two of those questions as a group. Short, repeated exposure to the document turns it from a compliance artifact into a trusted reference.

Building Practical Chemical Handling Procedures

Written procedures help remove guesswork from daily work. A practical GHS Hazard Communication Basics course should help supervisors translate theory into clear steps for their teams.

Effective procedures break tasks into simple actions: verifying labels before use, checking containers for damage, selecting the right PPE, controlling ignition sources, and confirming adequate ventilation.

Storage procedures address segregation of incompatible materials, housekeeping standards, and the degree of fill required before containers are moved to waste streams.

Supervisors can involve workers in the development or updating of procedures. Ask experienced team members where people tend to improvise or cut corners. Those are areas that need clearer steps or better tools.

When crews feel they have helped shape the procedure, they are more likely to follow it and speak up when something does not match the written steps.

Communication, Coaching, And Toolbox Talks

Hazard communication is not just a binder or an online module. It is an ongoing conversation. Supervisors are the main voice in that conversation.

Short, focused toolbox talks are among the most effective ways to maintain familiarity with GHS concepts. Instead of broad lectures, pick one concrete topic at a time: one pictogram, one common product, or one section of an SDS.

Use real examples from the current job rather than generic stock photos. Ask workers questions, invite stories about near misses, and encourage them to point out labels they see around them.

Coaching is just as important. When a supervisor notices an individual working without the right PPE or using an unlabeled container, that moment is an opportunity to teach, not just to correct.

Connect the observation back to the hazard communication basics covered in training, so people see that the rules are not random; they match real chemical risks.

Incident Response And Learning From Near Misses

Even with proper training, spills, splashes, and unexpected reactions can still occur. A GHS basics course should provide supervisors with a clear checklist for those moments.

Key elements include raising the alarm, protecting people first, isolating the area if necessary, identifying the chemical involved using labels and SDS, and following recommended first-aid and cleanup procedures. Supervisors should know where spill kits are located, whom to contact for additional assistance, and how to document the incident.

Near misses deserve attention as well. A lid left loose on a corrosive drum or a mislabeled bottle that is caught just in time is a learning opportunity.

Supervisors can discuss these events in team meetings, review the applicable label or SDS, and agree on simple changes in practice. Over time, this approach fosters a culture in which people speak up early rather than remaining silent until something serious occurs.

Common Supervisor Mistakes And How To Avoid Them

Even experienced supervisors can fall into patterns that weaken hazard communication. Recognizing these patterns is the first step to changing them.

One frequent issue is assuming that initial training is enough. Workers forget details, new products arrive, and shortcuts creep in.

Without refreshers and reminders, knowledge fades. Another problem is the acceptance of poor labeling on secondary containers, such as handwritten codes that only one person can understand.

Supervisors sometimes keep SDS access technically available but not truly usable, for example, by storing a binder in a locked office or by using a digital system that no one can access quickly.

There can also be gaps when contractors or temporary workers are present and do not receive the same level of information. Addressing these issues does not require complex projects; it requires consistent attention and willingness to ask, “If I were new here, would this setup make sense to me?”

Moving From Training To Everyday Safety Habits

Hazard communication is often described as “right to know,” but supervisors carry a responsibility that extends beyond legal obligation. They shape how safe workers feel speaking up, asking questions, and refusing unsafe shortcuts.

When leaders use the language of GHS daily, labels and SDSs cease to be background noise and become shared tools.

A strong basics course gives supervisors the building blocks. The real impact occurs when those blocks appear in pre-job briefings, walkarounds, incident responses, and conversations with new hires. Small, steady changes in how information is shared can prevent injuries that never appear in statistics.

The next time you review a chemical label or open an SDS with your team, you are not only meeting a requirement; you are setting the tone for how your workplace treats health and safety.