The first time I realized how fast a “small” chemical mix-up can snowball, it was over something ordinary: a spray bottle with no label. A new custodian grabbed it from a cart, assumed it was glass cleaner, and used it in a cramped restroom with poor airflow. Within minutes, his eyes were burning and he was coughing hard enough to stop work. When we traced it back, the bottle had been refilled with a stronger disinfectant. No label. No signal word. No quick way to confirm what it was or how to handle it.

That’s the reality behind hazard communication violations. They rarely announce themselves with drama. Instead, they appear as missing or unclear labels, outdated Safety Data Sheets (SDS), training that never quite sticks, or a written program that sits untouched. Yet these gaps can lead to injuries, chemical exposures, costly citations, and a workforce that loses trust in the safety system.

This is where completing a GHS HazCom course makes all the difference. Training helps workers understand labels, identify chemical hazards, read SDS information, and respond safely to unexpected exposures. Most HazCom problems are preventable with these practical skills, clear ownership, and a system designed for real workdays—not just perfect paperwork. A properly trained team can spot risks, choose the right PPE, and act with confidence before a “small” mix-up becomes a major incident.

Why Hazard Communication Gaps Happen In Real Workplaces

Hazard communication is supposed to feel like a well-lit map: anyone can glance at it and know where the hazards are, what they mean, and what to do next. In many workplaces, the map exists, but it is taped to the wall behind a stack of boxes. Work moves quickly, products change, vendors swap formulas, and departments borrow chemicals from each other “just for today.”

Another common cause is handoff failure. One person orders chemicals, another stores them, a supervisor trains the crew, and a third-party contractor shows up after hours with their own products. If no one owns the full chain, the system develops hairline cracks that widen over time. Fixing HazCom is often less about adding more rules and more about building a simple rhythm: inventory, label, SDS access, training, and verification.

hazard communication violations That OSHA Cites Again And Again

Federal OSHA regularly lists Hazard Communication (29 CFR 1910.1200) among the most frequently cited standards. OSHA’s own “Top 10 Most Frequently Cited Standards” list includes Hazard Communication in the top tier, signaling how often inspectors find gaps that matter.

What inspectors flag is not just “missing paperwork.” Many citations point to the basics not working at the point of use: a written program that does not match reality, containers that are not labeled, SDS libraries employees cannot access quickly, and training that is too generic to guide safe behavior. In FY 2025 reporting, one of the most cited HazCom sections highlighted the written program requirement (1910.1200(e)(1)), reinforcing how often workplaces fall short on the foundation.

Violation 1: A Written HazCom Program That Does Not Match The Floor

A written HazCom program should read like instructions for your exact workplace, not a template with blanks half-filled. The most common failure is having a program that says the right things while the daily routine says something else. If the document claims “all containers are labeled,” but secondary bottles sit unlabeled on carts, the program is not doing its job.

Fix this by writing the program around real workflows. Include who creates and updates the chemical inventory, where SDS are stored, how labeling is handled for secondary containers, and what happens when a new chemical arrives. Then tie it to accountability: one owner for the program, and named backups when that person is out.

Bullet-proofing actions you can take this week:

- Assign one program owner and one backup, with calendar reminders for quarterly reviews.

- Add a one-page “how we do it here” summary that matches your floor routines.

- Document contractor coordination: what you require, what you provide, and who checks it.

After the update, walk the floor with the written program in hand. If you cannot point to each step in action, revise until you can.

Violation 2: Missing Or Wrong Labels On Primary And Secondary Containers

Labels are the workplace’s front-line language. When they are missing, smeared, or inaccurate, the hazard becomes invisible. This is especially common with secondary containers: spray bottles, squeeze bottles, small jars, and day-use buckets. People refill them, move quickly, and assume they will remember what is inside. Memory is not a control method.

The fix is to make labeling easier than skipping it. Provide durable labels, pre-printed workplace labels that match your GHS elements, and a clear rule for immediate labeling at the moment of transfer. If you allow temporary labels for short tasks, define exactly what “temporary” means and require disposal or relabeling at shift end.

A practical approach that sticks:

- Put labeling supplies where transfers actually happen (not in an office drawer).

- Use water-resistant labels for wet areas and chemical rooms.

- Add a quick supervisor check during shift start: “spot-check five containers.”

When labels become part of the same routine as putting on gloves, compliance rises without constant nagging.

Violation 3: Safety Data Sheets That Are Hard To Access When It Counts

An SDS library that requires three clicks, a password, and a hunt through outdated folders is not truly accessible. During an exposure or spill, people do not have time to play detective. They need immediate information: hazards, first aid, PPE, and spill response guidance.

Fix this by designing for speed. Keep SDS available in two ways: a digital system that works on the floor, and a physical backup in the highest-risk areas. Make sure employees know exactly where both are and can retrieve them without asking permission.

Here’s a bullet-focused SDS upgrade that reduces friction:

- Post QR codes in chemical storage areas that link to the correct SDS folder.

- Keep a printed “SDS index” by product name and common nickname.

- Test access monthly by asking a random employee to pull an SDS in under 60 seconds.

If they cannot do it, the system needs a redesign, not another memo.

Violation 4: Chemical Inventory Drift And “Mystery Products”

Chemical inventories often start strong and slowly go stale. A department orders a new degreaser, a supervisor brings in a specialty adhesive, or someone stores an old product “just in case.” Over time, you end up with mystery bottles, expired products, and chemicals nobody remembers ordering. That creates risk and invites citations.

The fix is to treat chemical inventory like food in a fridge. If you do not know what it is, how old it is, and why it is there, it does not belong in active storage. Build a recurring inventory habit and connect it to purchasing so new chemicals cannot slip in without review.

Two paragraphs of effort that pay off: start with a quarterly inventory walk, then tighten to monthly in high-chemical areas. Tag unknowns immediately, quarantine them, and resolve them within a set time window. Each “mystery product” you remove is one less exposure scenario waiting for the wrong moment.

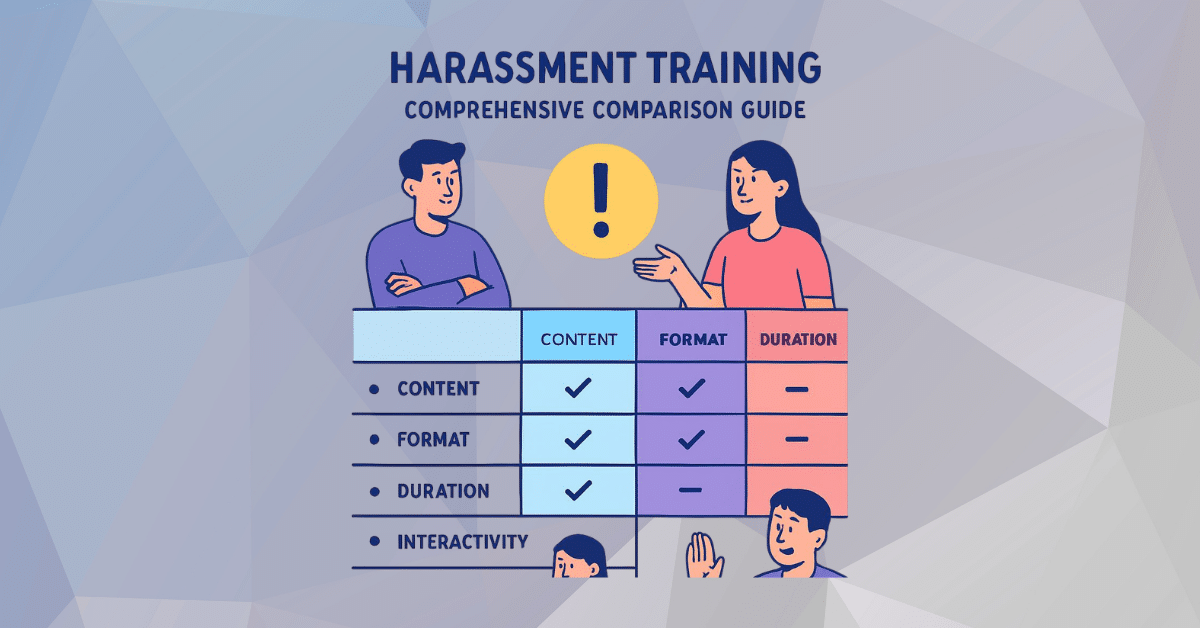

Violation 5: Training That Checks A Box But Does Not Change Behavior

Training fails when it stays abstract. Employees hear about pictograms and hazard classes, then return to a job where the real questions are practical: “Can I mix these two cleaners?” “What do I do if it splashes?” “Which gloves are right for this solvent?” When training does not answer those, people fill the gaps with guesses.

One powerful improvement is scenario-based learning using your actual products and tasks. Bring real containers (or photos), walk through label elements, and practice finding the relevant SDS sections. Then connect it to muscle memory: where the eyewash is, what to do first in an exposure, and how to report a near-miss.

This is also where training new hires on chemical safety can make or break your program. If a new employee’s first week includes clear chemical routines, they adopt them as “how we do things.” If their first week is rushed shadowing with no structure, shortcuts become the norm.

Violation 6: Contractor And Temporary Worker Communication Breakdowns

Contractors often bring chemicals on-site: sealants, cleaners, fuels, coatings. Temporary workers often move between departments and may not know where SDS are kept or which products are used in each area. When communication is weak, hazards cross boundaries like smoke through a doorway.

Fix this with a simple intake and orientation routine. Contractors should provide SDS for chemicals they bring, and you should provide your site rules: storage limits, labeling expectations, and disposal procedures. Temporary workers should get a short HazCom orientation tailored to the department they are assigned to, not a one-size lecture.

Make it practical: keep a one-page contractor chemical checklist and require sign-off before work begins. For temps, use a 10-minute “find it fast” tour: chemical storage, SDS access, eyewash, spill kit, and who to call.

Violation 7: PPE Guidance That Is Vague Or Inconsistent

Telling employees to “wear PPE” is like telling a driver to “be careful.” It sounds responsible, but it does not guide action. PPE must match the chemical and the task. Gloves that work for one product can fail quickly with another. Eye protection needs to fit the splash risk. Respirators require a separate program when needed, and misuse can create a false sense of safety.

The fix is specificity. For each commonly used chemical, identify required PPE based on SDS guidance and your exposure potential. Then post task-based PPE cues where the work happens. When employees see “this task, this PPE,” uncertainty drops.

A bullet set that helps supervisors enforce consistently:

- Create a PPE matrix for top 20 chemicals and top 10 tasks.

- Stock the PPE you require, in the sizes people actually use.

- Replace “optional” language with clear expectations and exceptions.

Consistency builds trust. People comply more when the rule feels tied to real risk, not personal preference.

Violation 8: Weak Spill And Exposure Response Practice

Some workplaces have spill kits that look great until you open them: missing absorbent, expired neutralizer, or gloves that do not fit anyone. Others have an eyewash station that is blocked by a pallet. The plan exists, but the moment arrives and the plan cannot move.

Fix this by practicing the first steps. Walk teams through “what happens in the first minute” for splashes, inhalation, and small spills. Then verify the tools: accessible kits, stocked supplies, clear reporting lines, and posted emergency numbers.

Keep this section from turning into a giant drill schedule by focusing on short, repeatable routines. A 5-minute monthly micro-drill beats a yearly training that everyone forgets.

What Citations Can Cost And Why Prevention Beats Cleanup

Citations can bring direct costs, but the hidden costs often sting more: downtime, re-training, reputation damage, and employee anxiety that lingers after an incident. OSHA publishes maximum penalty amounts that can be assessed after the annual adjustment. For federal OSHA, the maximum for a serious or other-than-serious violation is listed at $16,550 per violation, and willful or repeated violations can reach $165,514 per violation.

If you operate in California, Cal/OSHA penalty amounts and classifications can differ, and the state publishes its own updates for civil penalties. That’s one reason multi-state employers should avoid “one binder for everyone” and instead align programs to each jurisdiction’s requirements and enforcement patterns.

A Simple Fix-It Playbook You Can Run In 30 Days

You do not need a perfection project. You need a steady cadence that keeps the program alive. Think of hazard communication like maintaining brakes on a vehicle: you do not wait for failure, you inspect, adjust, and replace worn parts before the downhill stretch.

Week-by-week playbook:

- Week 1: Inventory walk, quarantine unknowns, remove expired products, confirm SDS coverage.

- Week 2: Labeling reset, stock supplies, add secondary container labels at points of transfer.

- Week 3: Written program edit to match real workflow, assign owner, set review dates.

- Week 4: Scenario-based training using your top chemicals, plus a floor test: “show me where the SDS is.”

End the month with verification. Randomly select three employees and ask them to: identify a label element, pull an SDS fast, and describe first steps for a splash. Their answers will tell you what your paperwork cannot.

Closing Takeaway And Next Step

Hazard communication is not meant to be a binder on a shelf. It’s meant to be a shared language that makes chemicals less mysterious and work more predictable. When labels are clear, SDS are easy to reach, inventories are accurate, and training is tied to real tasks, you reduce exposures and build a workplace where people feel protected rather than policed.

Pick one area this week where you know the system is thin, maybe secondary container labels or SDS access, and fix that first. Small repairs, done consistently, keep minor gaps from becoming the next near-miss story you never wanted to tell.

FAQ

What are the most common hazard communication violations employers get cited for?

The most common hazard communication violations usually involve basics that break down on the floor: incomplete written programs, missing or incorrect container labels, SDS that employees cannot access quickly, and training that is too generic to guide daily tasks. Inspectors often look for consistency between what your program says and what employees actually do. If your written process and real routine don’t match, that gap is where citations and incidents often begin.

How can I fix hazard communication violations without overhauling everything?

Start with the highest-friction points: labeling supplies where chemical transfers happen, SDS access that works in under a minute, and a chemical inventory that removes unknown or expired products. Then update the written program so it matches your real workflow and assigns a clear owner. Most hazard communication violations shrink fast when you focus on practical routines and verification, not extra paperwork that no one uses.

What should a written HazCom program include to avoid violations?

A strong written program explains how your workplace handles labels, Safety Data Sheets, employee training, and chemical inventory management. It should name responsible roles, describe how new chemicals are approved, and explain how secondary containers are labeled. It should also cover contractor coordination if outside crews bring chemicals on-site. Many hazard communication violations happen when the program is generic and doesn’t reflect your actual processes.

How often should we review labels, SDS, and our chemical inventory?

A quarterly review is a good baseline for most workplaces, with monthly checks in higher-chemical areas like maintenance shops, labs, or production lines. Labels should be checked continuously through quick spot-checks, especially on secondary containers. SDS libraries should be tested regularly by having employees pull an SDS during normal work, not just during audits. Regular reviews prevent hazard communication violations from building quietly over time.

What’s the best way to confirm employees really understand HazCom training?

Use short, task-based checks instead of relying only on sign-in sheets. Ask employees to explain a label pictogram on a product they use, locate the SDS quickly, and describe first steps for a splash or inhalation concern. Rotate these checks across shifts so you see the full picture. When employees can demonstrate the basics in real time, you’re less likely to face hazard communication violations and more likely to prevent exposures.