I still remember a day early in my career when a kid who normally talked a mile a minute barely spoke at all. Nothing “movie dramatic” happened. No big disclosure. Just a quiet change, a flinch when an adult moved too fast, and a vague comment about not wanting to go home. I went back to my desk and tried to talk myself out of what I was feeling. Maybe I was tired. Maybe I was reading into it. Maybe it was none of my business.

That is the space where real reporting decisions live. Not in neat stories, but in uncomfortable instincts. National Child Abuse Mandated Reporter Training (MRT) exists to guide professionals through these moments, emphasizing that child abuse reporting laws are designed so a child’s safety does not depend on an adult’s certainty. The law sets expectations for what to do when concern shows up, even when the full picture is missing.

Why Reporting Laws Exist And What They Ask Of You

Child abuse reporting laws are built on a simple reality: kids are not always able to protect themselves or explain harm clearly. Fear, loyalty, confusion, or pressure from adults can keep them silent. In many cases, the first “signal” is not a statement. It is behavior, mood, injuries, or a pattern that does not sit right.

These laws do not ask you to solve the case. They ask you to pass concern to the right system. That is a different job than investigating, interviewing, or proving anything. Reporting is a doorway to help, not a verdict. When adults treat reporting as a personal accusation, they hesitate. When adults treat it as a safety step, they act faster and with less panic.

Who Usually Has A Legal Duty To Report

Mandated reporter lists vary by state, but the same groups show up again and again because they are positioned to notice changes in children. Schools, healthcare settings, youth programs, counseling offices, and social services all see kids in ways that reveal patterns over time.

Common mandated reporters often include teachers and school staff, doctors and nurses, therapists and counselors, childcare providers, social workers, case managers, and law enforcement. Some states also require any adult to report suspected abuse, regardless of job title. Even when a person is not legally mandated, an employer may still require reporting as part of policy and duty of care.

If your workplace serves children, it helps to treat mandated reporting like fire safety. Everyone should know the basics, even if only one person “owns” the binder. The moment you need this information is usually the moment you are too stressed to go hunting for it.

What Reasonable Suspicion Looks Like In Real Life

Most people freeze because they think reporting requires certainty. In reality, suspicion usually builds in small layers. It might begin with a child who suddenly becomes clingy, aggressive, or unusually withdrawn. It might be a change in hygiene, hunger, sleepiness, or attendance. It might be injuries that keep appearing with explanations that do not line up with a child’s developmental stage.

Reasonable suspicion is not about being dramatic. It is about being honest with what you are seeing and hearing. One sign alone rarely tells the story, but patterns matter. Context matters. Your role is to notice what you can and speak up when it crosses the line into concern.

Here are examples of observations that commonly contribute to suspicion, especially when they repeat or cluster:

- Frequent unexplained bruises or injuries in different stages of healing

- A child fearful of a specific adult or desperate to avoid going home

- Sexualized language or behavior that does not match the child’s age

- Chronic lack of supervision, frequent hunger, or weather-inappropriate clothing

- Sudden changes in mood, grades, sleep, or social behavior

After noticing signs, many adults want to “check with someone” until the feeling goes away. It is fine to consult your internal reporting lead for process questions, but the decision to report should not be delayed while you seek emotional reassurance.

Child Abuse Reporting Procedures

Child abuse reporting procedures are the practical steps you take once reasonable suspicion exists. They are meant to work under pressure, which is why they are usually simple: report promptly, share facts, and let investigators handle the investigation. You are passing concern forward, not building a case.

In many places, the process begins with a phone call to a child protection hotline or a designated reporting agency. Some jurisdictions allow online reporting for certain situations. Many also require written follow-up after an initial call. Your workplace may have an internal flow, but legal timelines come first.

A grounded way to think about child abuse reporting procedures is this sequence:

- Identify the correct reporting channel for your area and situation

- Report as soon as possible after suspicion forms

- Share what you observed and what was said, using plain, factual language

- Document the date, time, and method of your report

- Follow internal notification rules after the external report, unless the policy delays the report

Child abuse reporting procedures feel less scary when they are treated like a standard safety routine. When staff only learn them “in the moment,” emotions take over and the process gets messy.

What To Do When A Child Tells You Something Directly

When a child discloses, adults often feel two impulses at once: protect the child and get every detail. The first impulse is healthy. The second can cause problems. Children can feel interrogated quickly, and leading questions can muddy later interviews.

The most helpful thing you can offer is steadiness. Listen. Keep your face calm. Let the child speak in their own words. Simple phrases land well, like “I’m glad you told me” and “You didn’t do anything wrong.” Be honest that you cannot keep it secret, because your job is to get help.

A good guideline is to ask only what you need to make a report, and stop. If you ask questions, keep them open and neutral. Avoid “why” questions, avoid guessing, and avoid pushing for a timeline. Your report can be based on what the child chose to share plus your observations.

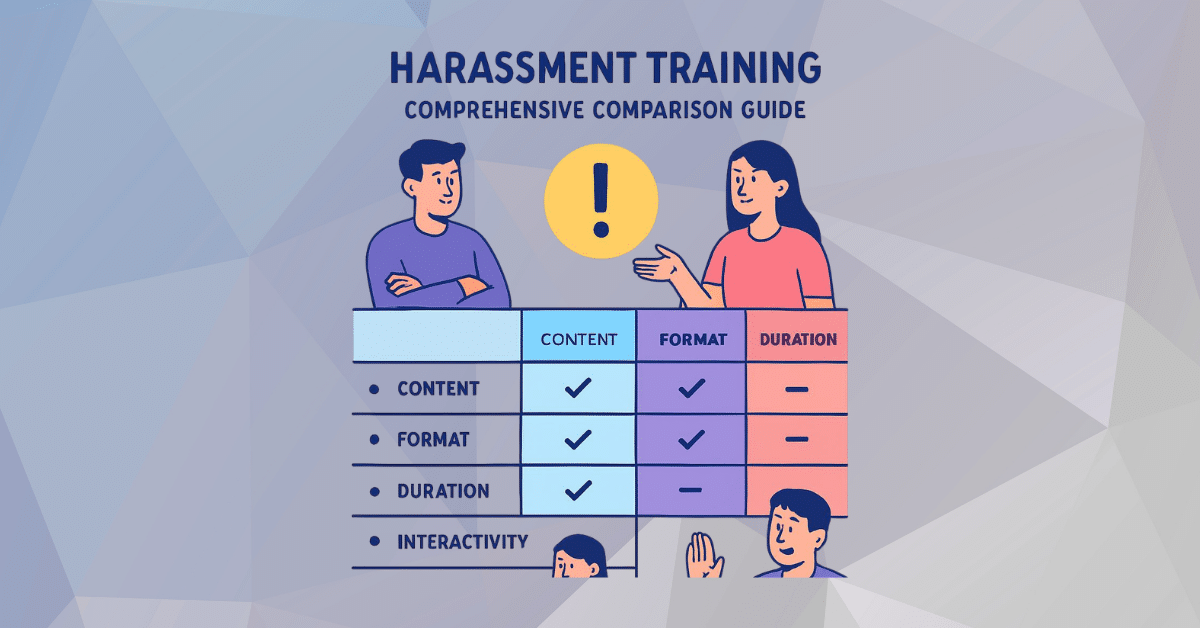

When To Call Law Enforcement Versus Child Protective Services

People often worry about choosing the “wrong” agency. The clearest dividing line is immediate danger. If a child is in urgent risk right now, law enforcement may be appropriate along with child protective services. If the concern is serious but not an active emergency, many reports begin with CPS.

This is another reason workplaces should have a posted, plain-language protocol. In a high-stress moment, it is easy to overthink. It is also easy to underreact. A protocol reduces that mental tug-of-war and helps staff act consistently.

Even when you contact one agency first, that agency can coordinate with others. Your responsibility is to report through the available channel and document what you did. The system can route the case from there.

Documentation That Protects The Child And Protects You

Documentation is where good intentions can get messy. Under stress, people add opinions, guess motives, or write like they are trying to “prove” something. That backfires. Clean notes stick to what happened, not what you think it means.

Write down what you observed, when you observed it, and what the child said in their own words when possible. Record dates, times, and who was present. Then record when you made the report, how you made it, and any reference number you received.

This is also where harassment training recordkeeping habits can help an organization. When teams are already used to documenting sensitive workplace issues with clarity and limited sharing, they tend to handle mandated reporting with less chaos. The skill is the same: factual notes, tight access, and consistent process.

Confidentiality, Good Faith, And Common Fears

A lot of hesitation comes from fear of being wrong. Another fear is backlash from families, colleagues, or supervisors. Most reporting frameworks recognize those fears and include protections for good faith reporting. The point is to encourage action when concern exists, not punish adults for not having certainty.

Confidentiality also matters for safety and trust. Reporting details should not become gossip, and they should not be discussed widely “so everyone knows.” Share only what your role requires, and only with those who truly need to know to keep a child safe or to follow policy.

If your workplace culture makes reporting feel risky, that is a leadership issue, not an employee issue. A healthy culture treats reporting like a professional duty and supports staff who act responsibly.

Training That Makes Reporting Feel Less Terrifying

Training is the difference between “I think I should report” and “I know what to do next.” It also helps adults separate their emotional reaction from their professional role. Many people carry the belief that reporting means accusing. Training reframes reporting as a safety relay.

Some workplaces use structured courses such as National Child Abuse Mandated Reporter Training MRT to reinforce definitions, role expectations, and basic steps. The value is not fancy wording. The value is repetition and clarity, so that when a real situation happens, people do not freeze.

The strongest training also includes practice scenarios that feel real, like a child disclosing indirectly, a caregiver giving inconsistent explanations, or staff disagreeing about whether something “counts.” Those are the moments people actually face.

Special Situations That Create Confusion

Certain settings create extra complexity. Schools may have multiple staff who each see a piece of the pattern. Healthcare settings may see injuries that need medical documentation. Youth programs may rely on volunteers who worry they lack authority. Custody disputes can create noise around reports, which makes staff anxious about being manipulated.

In these settings, clarity is your friend. Use child abuse reporting procedures as written, focus on facts, and avoid getting pulled into arguments about intent or family conflict. Your job is not to referee adult narratives. Your job is to protect a child by reporting concern.

It also helps to set expectations ahead of time, like posting hotline information, defining who helps with process questions, and teaching staff how to respond to disclosures. A plan does not remove emotion, but it reduces confusion.

Supporting A Child After You Report

Filing a report can feel like turning on a bright light. Some children feel relief. Others feel fear, shame, or anger. Some act like nothing happened. Your role after reporting depends on your setting, but the emotional approach stays similar: keep routines steady, treat the child with normal dignity, and avoid repeatedly bringing the topic up.

Support often looks quiet. It can be as simple as being predictable, watching for bullying or social fallout, and giving the child a calm space when they feel overwhelmed. It can also include coordinating with the right internal staff to maintain safety without exposing details widely.

Adults also need support after reporting. The weight is real, and it can show up as sleep disruption, irritability, or second-guessing. A workplace that takes reporting seriously also takes staff wellbeing seriously, because burned-out staff miss signs.

Building A Workplace That Makes Reporting Easier

The best reporting outcomes do not come from heroic individuals. They come from systems that are ready before anything happens. That includes clear policies, posted contacts, role-based training, and a culture that treats reporting as a normal safety act.

It also helps to run quick refreshers a few times a year. People forget details, and turnover is constant. A five-minute review of child abuse reporting procedures can prevent a five-hour spiral during a real incident.

When staff know the steps and feel supported, reporting becomes less about fear and more about care. That is how you protect children consistently.

Conclusion

Most mandated reporters never forget the first time they had to act on a suspicion. It can feel heavy, and it can feel lonely if the workplace culture is unclear or judgmental. Child abuse reporting laws were written to keep the responsibility from living only in a person’s gut.

If you take one idea from this, let it be this: you do not need certainty to report. You need reasonable suspicion, a clear process, and the willingness to choose safety over silence. When adults act early and consistently, children have a better chance of getting help before harm grows.

FAQ

What Are Child Abuse Reporting Procedures If I Only Have A Few Details?

Child abuse reporting procedures do not require a perfect story. If you have reasonable suspicion, you report what you observed and what you heard, even if the details are incomplete. Share identifying information you have, describe the concern in plain language, and document when you made the report. The agency receiving the report can gather more information through its own process. Your job is to raise the safety flag, not finish the investigation.

When Should Child Abuse Reporting Procedures Be Started?

Child abuse reporting procedures should begin once concern reaches reasonable suspicion. That can happen through a disclosure, repeated signs, or a pattern you cannot ignore. You do not need proof, confirmation from coworkers, or a supervisor’s permission. If you wait until you feel certain, you may be waiting while a child stays at risk. Reporting is a safety step designed for early action, not a final conclusion.

Who Is Responsible For Following Child Abuse Reporting Procedures At Work?

In many cases, the person who observes the concern is responsible for following child abuse reporting procedures, especially if they are a mandated reporter. Some workplaces designate a reporting lead to help with process questions, but that does not always remove individual legal obligations. If you are unsure, learn your role ahead of time, know where the reporting numbers are posted, and clarify internal steps that happen after the external report is made.

What Should I Write Down While Following Child Abuse Reporting Procedures?

When following child abuse reporting procedures, document facts and timing. Write what you observed, where it happened, when it happened, and who was present. If the child spoke, record their words as closely as you can, without adding interpretation. Then document when you reported, how you reported, and any confirmation details you received. Keep notes professional and limited, because documentation may later be reviewed by agencies or leadership.

What Happens After Child Abuse Reporting Procedures Are Completed?

After child abuse reporting procedures are completed, the agency reviews the report and decides what response is appropriate. You may not receive updates due to privacy rules, even if you want reassurance. Your next step is usually internal: document that you reported, follow your workplace’s notification policy, and continue supporting the child through stable routines and respectful care. If new concerns appear later, you can follow child abuse reporting procedures again.