The first time we realize we might need to report suspected abuse, it rarely feels clean or clear. It usually feels like a knot in the stomach. A child says something that lands wrong. A bruise shows up again. A story changes in small ways. We go home that night replaying the moment, trying to talk ourselves into the idea that we misread it.

I still remember a conversation years ago in a staff hallway, the kind that happens in a hushed voice near a copy machine. A coworker mentioned a child who flinched when an adult raised their hand to wave. Nothing dramatic happened in that hallway. No shouting, no sirens. Just that small detail that stayed with us. The hardest part was not the paperwork. The hardest part was accepting that “maybe” was enough to act.

That is why child abuse reporting procedures exist, and why National Child Abuse Mandated Reporter Training (MRT) emphasizes responding to reasonable suspicion rather than waiting for certainty. They are built for real life, where warning signs can be quiet, where we may only hold a piece of the picture, and where a child’s safety can depend on an adult choosing action over doubt.

What A Report Is And What It Is Not

A report is not a verdict. It is not an accusation you have to prove. It is a way to hand a concern to professionals whose job is to assess child safety and decide what comes next. When people think reporting means “ruining someone’s life,” hesitation grows and children can be left waiting.

A report is more like turning on a porch light when you hear something outside. You are not claiming you know exactly what is happening. You are saying, “Something might be wrong, and it deserves a closer look.” That mindset keeps the focus where it belongs: on the child’s well-being, not on our fear of being imperfect.

When Concern Becomes Reasonable Suspicion

Many people freeze because they want certainty. In real settings, certainty is rare. Most policies and laws use a standard closer to “reasonable suspicion,” meaning what you saw or heard makes abuse or neglect a plausible explanation, even if you cannot confirm it.

Reasonable suspicion often shows up as a pattern, not a single moment. A child who was once talkative becomes unusually quiet. Injuries appear repeatedly with explanations that shift. A child seems terrified about going home on a particular day. None of these signs require you to diagnose what is happening. They call for you to notice and respond.

It helps to separate observation from interpretation. We can report, “Child said, ‘I’m not allowed to tell,’ and began crying when asked about home.” We do not need to decide why the child said it. Investigators handle that part.

What To Do In The Moment When A Child Discloses

When a child starts to share something sensitive, adults often feel two urges at the same time: protect the child and gather details. The first urge is right. The second can cause problems. Too many questions, especially leading ones, can unintentionally shape what the child says and make later interviews harder.

Start with steadiness. Keep your face calm. Keep your voice even. Children watch our reactions closely, and panic can shut them down. Let them speak in their own words and keep your prompts simple.

Use supportive responses that do not promise outcomes you cannot control. Saying “I’m glad you told me” can help a child feel less alone. Saying “I’m going to get help” can be true without making guarantees you cannot make.

A Quick Pre-Report Checklist That Keeps You Grounded

Before you call a hotline or submit an online report, take a short pause to organize what you already know. This is not an investigation. It is a way to make your report clearer and more useful, especially when your heart is racing.

Write down the facts you personally observed and what was disclosed directly to you. If you are in a workplace, follow internal steps for notifying the right person, but do not let workplace habits slow you down if you are required to report promptly.

Here is a practical checklist to gather the essentials:

- The child’s full name, age, and current location if known

- Names of caregivers or involved adults, if known

- Date, time, and place of the concerning incident or disclosure

- Visible injuries described plainly (size, color, location on the body)

- Exact words the child used, written as closely as possible

- Any immediate safety risk, especially if the child may be returning to danger today

Once your notes are in place, you are ready to report with clarity instead of scrambling for details mid-call.

Most missed reports do not happen because someone does not care. They happen because someone hesitates. Fear of being wrong. Worry about backlash. The assumption that another adult will step in. The decision to wait just one more day.

This hesitation is how failure to report child abuse most often begins. Not with cruelty or neglect, but with uncertainty and delay.

But harm does not pause while we wait for reassurance. When concerns go unreported, children may remain in unsafe environments longer. Patterns of abuse stay hidden. Support services may never be activated. And the quiet weight of “I should have said something” can stay with a person for years.

Reporting is not about punishment. It is about opening the door to safety checks, intervention, and protection when needed. Reporting shifts the responsibility to trained professionals who can assess risk and provide help.

When we choose to report, we choose the child’s safety over our own discomfort. We choose action over silence—and prevention over regret.

How To File The Report Step By Step

Reporting methods vary by location and role, but most systems ask for similar information. The goal is to be specific, factual, and organized. If you are calling by phone, having your notes in front of you makes a real difference.

Begin with identifying details about the child and where the child can be located. Then explain what prompted your concern. Share what you observed, what you heard, and what the child said, without adding theories about motive. If you suspect neglect, describe the conditions or repeated patterns you have seen.

Close by asking what happens next and whether a written follow-up is required. Some roles require a written report after a phone call. Getting that instruction directly helps you stay compliant and reduces stress later.

What Makes A Report Strong And Useful

A strong report reads like a timeline. It is clear about dates, observations, and disclosures. It avoids guessing, labeling, or diagnosing. Investigators can work with facts. They cannot work well with assumptions.

If you are unsure about a detail, say so. Honest uncertainty is not a weakness. It is a sign you are sticking to what you actually know. This also protects you, because your report reflects good-faith reporting rather than speculation.

These details tend to help investigators evaluate urgency:

- Direct quotes from the child when possible

- Physical descriptions of injuries or conditions

- Changes in behavior that have a clear “before and after”

- Patterns you have personally observed across time

- Any reason you believe the child may be in danger right now

If you can share these details calmly and clearly, your report will be far more actionable.

Avoiding Common Mistakes Without Overthinking

Even experienced professionals can make missteps when emotions run high. The good news is most mistakes are preventable with a few simple habits.

One mistake is waiting for “enough” evidence, as if you are building a case. Another is asking too many questions, especially questions that suggest answers. A third is sharing information with coworkers who do not need to know, which can turn a safety action into workplace gossip.

To keep yourself on track, hold onto three anchors: report suspicion, document facts, protect privacy. If you stick to those, you are doing the job the system expects of you.

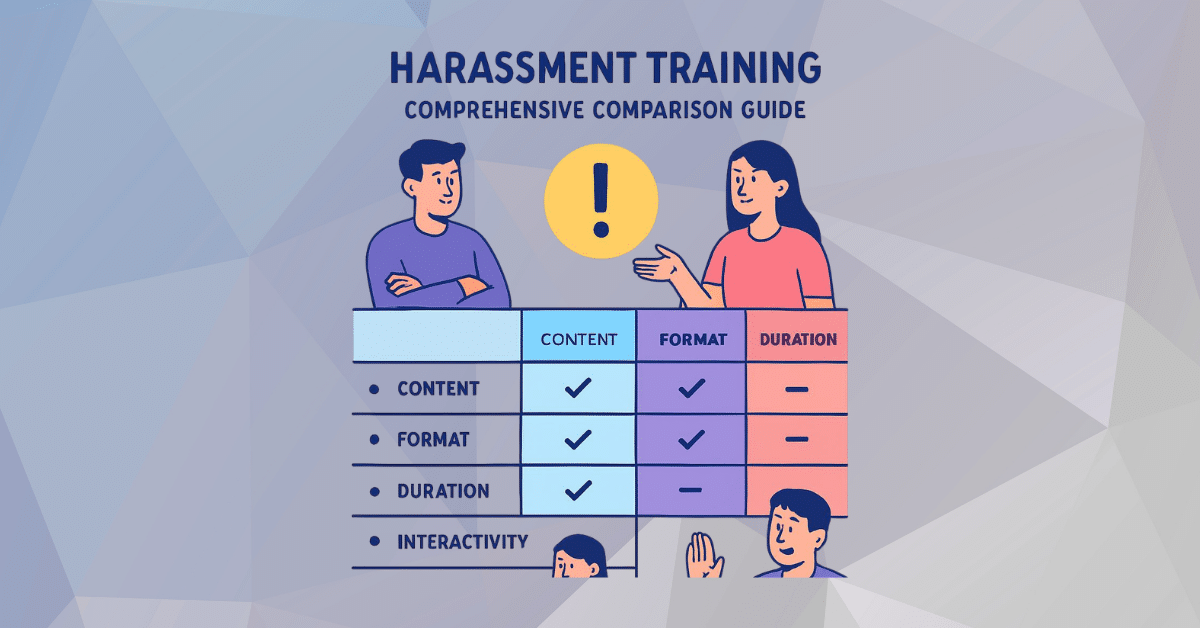

Documentation And Workplace Recordkeeping

Many workplaces have internal documentation requirements alongside external reporting. Those records should be factual, dated, and securely stored. Keep them focused on what you saw, what you heard, and what actions you took.

This is where harassment training recordkeeping practices can be a helpful comparison. Sensitive information should be limited to people with a legitimate need to know. Notes should be written in neutral language that can stand up to review. Opinions and rumors do not belong in official records.

If your organization has a chain of notification, treat it as support, not a gate. Internal process should help you act smoothly, not slow down reporting when time matters.

After You Report: What To Expect Emotionally And Practically

After a report is filed, agencies decide how to respond based on risk and criteria. Some cases lead to immediate action. Others may be screened in for further review, or combined with prior information. As a reporter, you may not receive detailed updates, and that lack of closure can be hard.

Many people feel a strange emotional aftertaste after reporting. Relief mixes with worry. You might second-guess every detail you shared. You might wonder if you did enough. Those feelings are common, especially for people who care deeply.

If you continue to interact with the child, keep documenting new observations and report again if new concerns arise. Reporting is not always a single event. Sometimes it is a series of safety actions over time.

Building Confidence Through Training And Practice

One reason reporting feels scary is that many people only learn it once, during onboarding, and never rehearse it again. Skills fade. The steps blur together. When a real moment hits, the brain can stall.

Practice restores confidence. Short scenario discussions, role-based checklists, and refresher training can help people act without freezing. Training also helps staff recognize the difference between supportive listening and accidental interviewing.

In some workplaces, National Child Abuse Mandated Reporter Training MRT is used to refresh knowledge and sharpen judgment in realistic situations. When training includes practical examples and documentation practice, it can make reporting feel like a clear process instead of a terrifying unknown.

Prevention Mindset: Small Habits That Protect Children

Reporting is reactive, but a prevention mindset is proactive. It means we stay alert to patterns, create safe opportunities for children to talk, and take notes when concerns arise rather than relying on memory.

Prevention can also be as simple as creating predictable routines that make changes visible. When you know what “normal” looks like for a child, it is easier to notice when something shifts. Children often communicate through behavior long before they use direct words.

If you work in a setting with children, build a culture where concerns can be voiced without ridicule. When adults feel supported, they report sooner. When adults feel judged, they stay quiet.

Closing Thoughts And A Call To Action

Filing a child abuse report the right way is not about being fearless. It is about being steady. It is choosing action when a child’s safety may be at stake, even when the situation feels messy and unclear.

Take ten minutes today to prepare for the moment you hope never comes. Write down your reporting channel, your internal steps, and the basics you should document. Talk through a simple scenario with a colleague or supervisor. Preparation turns panic into a plan.

When the moment arrives, you will not need perfect words. You will need a clear next step. This guide is here to help you take it.

FAQs

What if I hesitate and then realize later I should have reported?

That delay happens more often than people admit, usually because the situation felt unclear in the moment. If new information strengthens your concern, you can still report. Use your notes to describe what you observed and when. If you are worried about consequences tied to not reporting, focus on making the best decision now. Acting today can still protect a child who may be at risk.

Can I get in trouble for not reporting if I thought someone else already did?

Assumptions are risky in safety situations. In many roles, the duty to report is personal, meaning it does not vanish because someone else might act. If you are unsure, it is safer to report what you know. Keep your report factual and limited to your observations. That way you protect the child and reduce the chance of being pulled into a “who reported” confusion later.

How do I live with the fear that I might be wrong if I report?

That fear is real, especially for people who value fairness. Reporting is not a declaration that abuse is proven. It is a request for trained professionals to assess risk. If you stick to what you saw or what was disclosed, you are acting in good faith. Many people find peace in remembering this: silence can be far more damaging than a careful report.

What should I do if my supervisor discourages me from reporting?

Workplace pressure can show up in subtle ways: “Wait,” “Let’s talk first,” “We do not want drama.” If you are required to report, your responsibility remains yours. Follow internal steps when they support timely action, but do not let internal politics delay a safety report. Document your actions and keep your language neutral. Your job is child safety, not workplace comfort.

How can organizations reduce missed reports without scaring staff into overreacting?

Clear systems lower fear. Staff need simple checklists, short scenario practice, and guidance on how to document observations without guessing. Leaders also set the tone. When leadership treats reporting as a protective step rather than a personal accusation, staff feel safer acting early. A calm culture of reporting reduces missed concerns and also reduces panic, because people know exactly what to do.