I still remember the first time a student quietly said something that made my chest tighten. It was not shouted or dramatic. It was small, almost casual, like a pebble dropped into a still pond, and I could see the ripples forming before I even stood up. After the conversation ended, I did what many people do. I replayed every word, wondering if I heard it right and whether I’d respond the right way.

Then came the part no one talks about much: writing it down. My hands hesitated because documentation can feel like stepping onto a narrow bridge. You want to protect the child, protect the truth, and protect your professional role, all at once. That is why good documentation matters. It turns a heavy moment into a clear record that other professionals can follow without guessing.

Why Documentation Matters For Mandated Reporters

Documentation is not just “paperwork.” It is the story of what you observed, what was shared, and what you did next, written in a way that holds steady over time. Weeks later, your memory may blur. A clear record does not. It can support an investigation, help identify patterns, and show that you acted promptly and responsibly.

Think of documentation like a trail in fresh snow. If it’s clear, others can follow it without stepping into the wrong place. If it’s messy or filled with assumptions, people may misread what happened. Your role is to capture the trail, not to decide where it leads.

Mandated Reporter Documentation

Mandated reporter documentation works best when it reads like a clean window instead of a courtroom speech. You are not trying to persuade anyone. You are preserving facts and context so the right agencies and decision-makers can respond.

A strong record separates what you directly observed from what you were told. It uses neutral words, includes timelines, and keeps the focus on actions taken. When your notes stay grounded, they remain useful even if reviewed months later, when the moment is no longer fresh in anyone’s mind.

What A Strong Record Actually Includes

The goal is clarity. Your documentation should answer the basic questions a careful reader will have: who, what, when, where, and what happened next. If those pieces are present, your record becomes easier to trust and easier to act on.

Start with the facts you personally observed, then capture disclosures or reports in a clearly labeled way. If a child uses certain words, record them as closely as you can. If you summarize, make it obvious you are summarizing and not quoting.

Here are common elements to include:

- Date and time of the observation or disclosure

- Location and setting (classroom, clinic room, hallway, online platform, home visit area)

- Names and roles of people present

- Objective observations (behavior, tone, body language, injuries, condition of clothing)

- Direct quotes or clearly marked summaries of what the child said

- Any questions you asked, using simple neutral descriptions

- Actions taken (internal notification steps, report made, immediate safety support)

- Follow-up steps and any instructions you received through policy channels

After you list the details, add a short narrative paragraph that ties the timeline together. Keep it simple and factual.

What To Avoid Writing Down

Many people accidentally weaken their documentation by writing conclusions instead of observations. The instinct is understandable. When you feel concerned, you want to name it. But documentation holds up best when it stays close to what you saw and heard.

Avoid guessing causes, motives, or intent. Avoid diagnosing. Avoid labeling a caregiver or child with loaded terms. You can still document your concern by describing what raised that concern, without claiming you know why it happened.

Avoid including:

- Assumptions about how an injury happened

- Opinions about a caregiver’s character or parenting style

- Medical or psychological labels outside your training and role

- Gossip, unrelated family history, or community rumors

- Emotional language that sounds like a verdict

When you feel tempted to write a conclusion, ask yourself: “If someone else read this without me in the room, would they know what I actually saw?”

Timing And The Value Of Writing While It’s Fresh

Documentation is most accurate when it’s done soon after the observation or disclosure. Stress can distort memory, and details can slip away faster than people expect. Even small facts like the exact time, who was present, or the child’s exact wording can fade.

If you can, write brief notes immediately, then expand them once the child is safe and the moment has settled. If you cannot document right away, document as soon as practical and note the timing honestly. A transparent time gap is better than a “perfect” record created later with guessed details.

Two habits that help in real settings:

Write a quick factual outline right away, then return for a fuller narrative.

Use a consistent format so you don’t forget basics like times, locations, and next steps.

Language That Holds Up Under Pressure

Your words should be steady even when your emotions are not. Neutral language builds credibility and helps readers focus on what matters. Loaded language, even when well-intended, can create confusion and invite arguments about tone rather than facts.

Aim for description, not judgment. Replace labels with observable details. A good rule is to write as if you are describing a security camera clip, but with human context.

Examples of neutral phrasing:

“Child cried for several minutes and did not respond to prompts” instead of labeling the emotion.

“Caregiver raised voice and said, ‘Stop crying or I’ll give you something to cry about’” instead of guessing intent.

“Bruise approximately 2 inches, blue-purple, on left upper arm” instead of “suspicious bruise.”

“Child stated…” or “Child reported…” instead of “Child admitted…”

After the facts, include a second paragraph that documents what you did next. This is where your record becomes a clear chain, not just a snapshot.

Writing Down Disclosures With Care

When a child discloses something, the words matter. A small change in wording can change meaning. If you can capture the child’s phrasing as close as possible, do it. If you cannot quote word-for-word, write that you are summarizing and stick closely to what was said.

It also helps to document your own response briefly, especially if it relates to safety or reporting. Keep it short. Focus on what you did, not how you felt.

If the child uses unclear language, you can document clarifying questions, but keep them simple and non-leading. Write the question you asked and the answer given, without adding your interpretation.

Confidentiality And Record Handling

A strong record can become a weak link if it is not protected. Documentation often includes sensitive information that should be shared only with people who have a defined need to know under policy and law. Loose handling can harm the child’s privacy and cause problems for your organization.

Treat these records like something you would not want accidentally read aloud in a crowded room. That mental check can guide daily habits.

Helpful confidentiality practices:

Store records only in approved systems with access controls.

Avoid saving notes on personal devices or personal cloud accounts.

Limit printed copies and keep them locked when required.

Keep details out of casual conversations and group chats.

Share information only through the proper reporting channels.

Two paragraphs matter here because confidentiality is not only a policy topic. It’s also a trust topic. Children and families deserve to know that sensitive information is handled respectfully.

Templates And Documentation Tools That Reduce Mistakes

When adrenaline is high, templates can keep you from missing key details. They also help standardize documentation across staff, which reduces confusion and makes patterns easier to identify.

Still, templates should not flatten the story. Checkboxes alone cannot explain what happened. Pair structured fields with short narrative paragraphs that capture the timeline clearly.

Good tools often include:

Auto time stamps and edit logs

Separate fields for observed facts vs reported information

Space for direct quotes

A section for actions taken and reporting confirmation details where applicable

A place for addenda, so updates are documented without rewriting the original record

If your workplace does not have a template, creating a simple one-page outline can help you document with consistency.

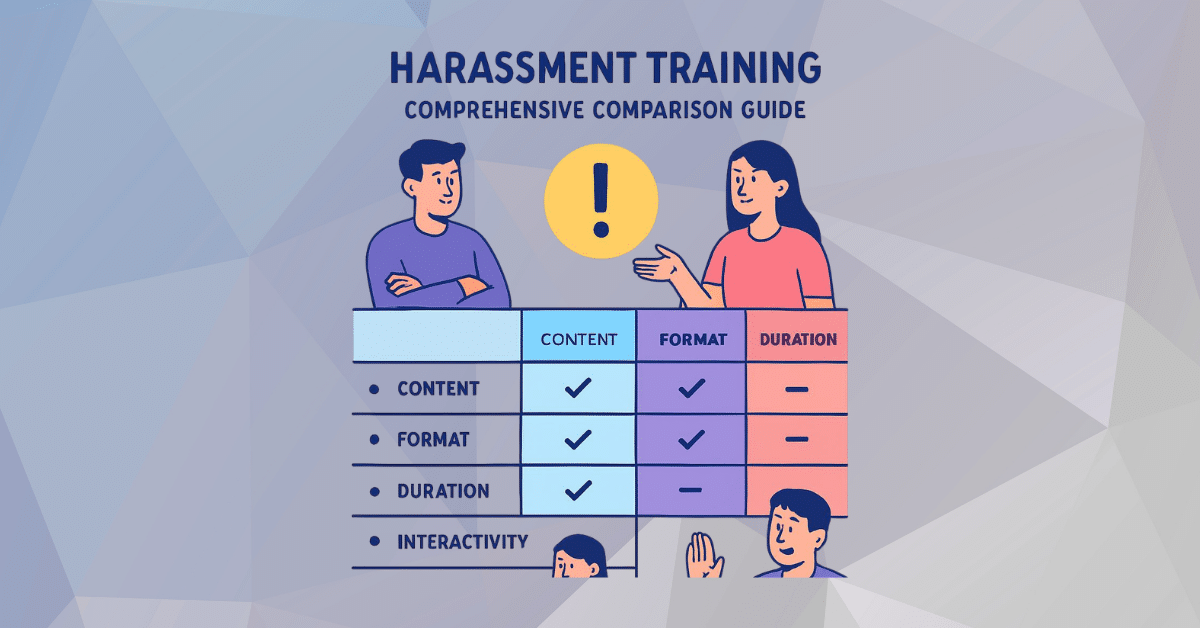

Coordination With Workplace Recordkeeping Systems

Many organizations run multiple compliance processes at the same time, and documentation can get misfiled when staff are juggling systems. It helps to know where child safety records belong so they do not end up mixed with unrelated logs.

For example, harassment training recordkeeping systems are often built for HR compliance and employee documentation, not for sensitive child safety reporting records. Keeping these channels separate supports confidentiality and prevents accidental access by people who do not have a need to know.

If you are unsure where documentation should live, follow your organization’s child safety protocol and document within the system designated for reporting concerns about minors.

Documenting Actions Taken Without Handing Off Responsibility

Some people think documentation is done once they tell a supervisor. In many settings, that assumption can create risk. Policies vary by jurisdiction and role, but your notes should clearly reflect your own actions and the steps you completed.

Strong documentation shows a chain of events that does not rely on “someone else will handle it.” It also reduces confusion when multiple staff members are involved.

A clear action record includes:

Who you notified internally and when

Whether you made a report through the required channels and when

Any confirmation details provided by the reporting system, if applicable

What immediate safety steps were taken in your setting

Any instructions you were given and how you followed them

Write it like a timeline someone could follow without calling you months later to ask, “What happened next?”

Corrections, Addenda, And Late Details

People worry that changing notes will make them look unreliable. The truth is that honest addenda often strengthen trust. If you remember a detail later, or you discover a time was incorrect, the best practice is to add an addendum rather than rewriting the original entry.

An addendum should be clearly labeled with the date and time it was written. It should state what is being corrected or clarified, and why. This keeps the record transparent.

A practical addendum format:

Date/time addendum written

Clarification or correction

Reason for the update

Your name/role as required by policy

This keeps documentation clean and shows integrity.

Documentation As Part Of A Prevention Culture

Documentation is usually discussed as a response tool, but it also supports prevention. Clear records help identify patterns that might not be obvious in one isolated moment. A single note can feel small, but multiple consistent notes can form a clearer picture over time.

This is where child abuse prevention training connects to daily practice. Training helps professionals recognize warning signs and understand reporting steps. Documentation captures what happened in real life, in real language, at real times. Together, they create a safer environment where concerns do not disappear into vague memory.

Prevention-oriented documentation habits include recording repeated concerns, noting context that affects safety, and documenting the supports offered in your setting without exaggeration or editorial tone.

Keeping Skills Current With Real Practice

Documentation improves with practice, feedback, and refreshers. Many people feel unsure until they have seen examples of strong documentation side by side with weaker documentation. That comparison helps staff notice how small word choices can change the meaning of a record.

Programs such as National Child Abuse Mandated Reporter Training MRT can support skill building by reinforcing reporting expectations, boundaries, and documentation habits for teams across education, healthcare, youth programs, and social services.

Practical ways to keep skills sharp:

Short refreshers that include documentation examples

Scenario practice that ends with writing a two-paragraph record

Clear guidance for new staff on where documentation is stored

A culture where questions are welcomed and answered with respect

Mini Scenarios That Show What Good Notes Look Like

Sometimes the hardest part is knowing how it should sound. Examples help, not because you should copy them, but because they show how to keep facts clear without adding conclusions.

Scenario 1: Disclosure with behavior

Paragraph one: “On 01/12 at 10:20 a.m. in the reading corner, student avoided eye contact and flinched when a book was placed on the table. When asked if they were okay, student stated, ‘Don’t tell him I told you. He gets mad.’”

Paragraph two: “I responded calmly and told student I may need to share with appropriate professionals to help keep them safe. At 10:35 a.m., I followed protocol by notifying [role] and documented the concern in the designated system. A report was made through required channels at 11:05 a.m.”

Scenario 2: Physical observation without conclusions

Paragraph one: “On 02/03 at 8:10 a.m., child arrived with a bruise approximately 1.5 inches on right cheekbone, blue-purple in color. Child stated, ‘I fell,’ and did not provide additional details when asked an open question about what happened.”

Paragraph two: “Child appeared tired during morning activities and laid head down twice. At 9:00 a.m., I followed reporting steps per policy and documented actions taken, including the time of the report.”

These examples stay factual, include quotes, and show action steps without claiming certainty that the reporter does not have.

Conclusion

Documentation can feel uncomfortable because it asks you to slow down in a moment when you want to act fast. But when your notes are clear, respectful, and grounded in what you observed, you give others the ability to respond with less confusion and more confidence. You also protect yourself by showing exactly what you did and when you did it.

If you want a simple next step, choose one documentation structure you will follow every time: facts, quotes, timeline, actions taken. Practice writing it in two solid paragraphs. The goal is not perfect writing. The goal is a record that honors the child’s safety and supports the reporting process with clarity.

FAQ

How Detailed Should Mandated Reporter Documentation Be?

Strong mandated reporter documentation should be detailed enough that someone else can understand what happened without needing your memory to fill gaps. Include dates, times, locations, who was present, what you observed, and what actions you took. If a child disclosed information, capture direct quotes when possible or label your summary clearly. Avoid extra background unless it directly connects to the concern and timeline.

Should Mandated Reporter Documentation Include My Opinions Or Suspicions?

It’s better to keep mandated reporter documentation focused on what you observed and what was reported to you. Opinions can distract from the facts and create disagreement about tone instead of content. If you need to explain why you reported, describe the specific observations or statements that raised concern. This shows the basis for action without turning the record into a conclusion that is not yours to make.

What If I Make A Mistake In Mandated Reporter Documentation?

Mistakes happen, especially in stressful situations. The safest practice is to add an addendum rather than rewriting the original entry. In your addendum, include the date and time you are updating the record, state what you are correcting, and explain how you confirmed the updated detail. This approach keeps mandated reporter documentation transparent and maintains trust in the integrity of the record.

Can I Share Mandated Reporter Documentation With Coworkers Or A Supervisor?

Share mandated reporter documentation only with people who have a defined role and a legitimate need to know under your policy and confidentiality rules. In many workplaces, you may notify a supervisor, but that does not mean the details should be widely shared. Keep documentation stored in approved systems, avoid informal conversations about sensitive details, and focus internal coordination on the steps required for safety and reporting.

How Can I Get Better At Writing Mandated Reporter Documentation Over Time?

The best way to improve mandated reporter documentation is to use a consistent structure and practice it. Write factual observations first, capture direct quotes, and document actions taken in a clear timeline. Reviewing sample scenarios and receiving feedback within appropriate confidentiality limits can help your writing feel more natural and accurate. Over time, you’ll develop a steady “facts-first” habit that reduces stress and supports better reporting outcomes.