Anti-retaliation problems rarely start with a cartoon villain move. They start with a manager trying to “fix the situation” fast, like grabbing a leaking pipe with bare hands. The intent might be to stop the mess, but the reaction leaves fingerprints everywhere, and those prints can become the story later.

I’ve seen the pattern play out in the same way: a complaint lands, the room temperature drops, and people begin making “small” adjustments that feel practical in the moment. A schedule shifts. A project gets reassigned. A tone changes in meetings. Weeks later, what felt like ordinary management suddenly looks like punishment for speaking up. That is where liability often grows.

Why Retaliation Claims Catch Employers Off Guard

Retaliation is often easier to allege than the underlying misconduct because it can be tied to visible workplace actions: hours, assignments, evaluations, discipline, access to training, and even social treatment. A harassment complaint can be hard to prove quickly, but a sudden demotion, a cut in shifts, or a new write-up is simple to point to.

Managers also underestimate how wide the “protected activity” umbrella can be. It can include reporting, participating as a witness, supporting a coworker, requesting an investigation, or pushing back on behavior that feels discriminatory. When you treat the complaint as a workplace event that triggers special care, you reduce the chance of turning an already stressful moment into a second injury.

How To Apply Anti-Retaliation Rules In New York In Real Manager Moments

Anti-Retaliation Rules In New York are not a technicality reserved for HR. They show up in ordinary decisions managers make every week, especially right after a complaint or investigation begins. Think of it like walking through wet cement: you can still move forward, but you need a planned path so you do not leave tracks that harden into evidence.

A practical way to handle this is to separate “workplace safety and stability” from “workplace consequences.” You can take steps to prevent contact, reduce tension, or protect operations, but those steps must be neutral, temporary when possible, and documented with a clear business reason that is not tied to the complaint.

Here are common areas where managers accidentally step over the line:

- Job changes: duties, hours, location, remote status, or reporting lines

- Opportunity changes: training, stretch projects, client access, overtime, promotion tracks

- Treatment changes: isolation, cold shoulder behavior, new scrutiny, public criticism

- Process changes: surprise discipline, performance plans, or harsher standards than peers

Mistake 1: Responding Like The Complaint Is A Character Judgment

A complaint can feel personal to a supervisor, especially if it involves someone on their team or someone they like and trust. The risk starts when the manager’s emotional response becomes workplace behavior, such as sarcasm, distancing, or “fine, then” decision-making. Even a subtle shift in tone can become part of a retaliation narrative.

Managers can protect themselves by using a simple mental rule: treat the report like a safety report, not a betrayal. The job is to keep the process clean. If you feel defensive, pause before speaking, and keep your conversations limited to operational needs and the reporting process.

Examples of high-risk manager reactions include:

- “Why are you doing this now?”

- “This is going to blow up the team.”

- “You’re making me look bad.”

- “We have to be careful around you.”

Mistake 2: “Helpful” Job Changes That Quietly Punish The Reporter

One of the fastest ways to create exposure is moving the reporting employee “for their own good” without their input or without exploring options. A schedule change that disrupts childcare, a location change that adds commute time, or removing someone from a visible project can look like a penalty, even if the manager meant to reduce conflict.

If you need to separate people, start with choices that do not harm the person who raised the concern. If a change must happen, explain the neutral business reason, offer options when possible, and keep it temporary while the situation is reviewed. In plain terms: do not solve the problem by shrinking the reporter’s job.

When separation is needed, safer options often include:

- Adjusting the alleged actor’s schedule or workstation instead of the reporter’s

- Adding a neutral intermediary for communication

- Offering voluntary alternatives rather than imposing changes

- Making changes time-limited, with a planned check-in date

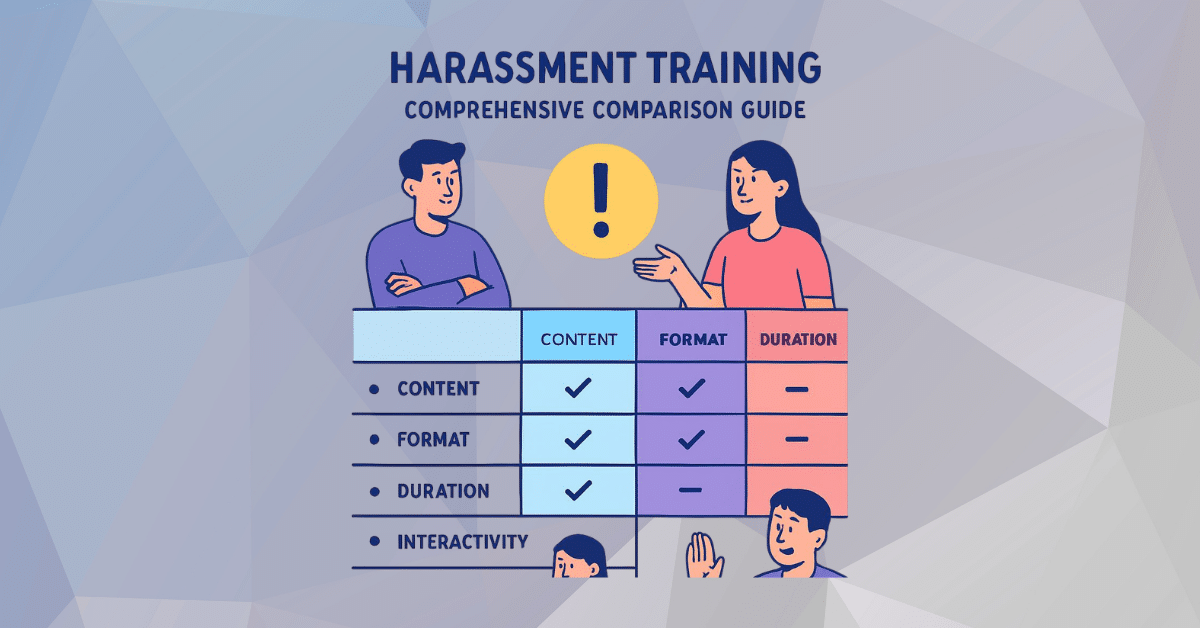

Mistake 3: Letting “Team Chatter” Become A Management Tool

Retaliation is not only formal discipline. It can be social pressure, exclusion, jokes, or comments that label someone as “a problem.” Managers sometimes allow this because it feels like peer dynamics, or they join in because they want the group to “move on.” That can turn into a claim that the workplace became hostile after a report.

The manager’s role is to stop the drip before it becomes a flood. Set expectations early: no gossip, no pile-ons, no speculation about outcomes. If the team needs a reset, focus on professionalism and respect, not on the report itself.

Common social retaliation patterns to watch for include:

- Meetings where the reporter is left off invites or copied emails

- Inside jokes, eye-rolling, or whispers when the person speaks

- Coworkers being encouraged to “keep distance”

- Managers over-sharing about the process, even indirectly

Mistake 4: Starting Performance Scrutiny Only After A Complaint

One of the most common manager mistakes is trying to “get the paperwork right” after a report. If an employee’s performance was truly an issue, the record should show consistent coaching and standards before the complaint. When discipline starts right after protected activity, it can look like a punishment that is dressed up as performance management.

This does not mean you cannot manage performance during an investigation. It means you must manage it the same way you would have the month before the complaint, with consistent expectations, comparable treatment to peers, and clear documentation that ties to objective outcomes.

A safer performance approach includes two parts:

- Separate timing: confirm what coaching or metrics existed before the complaint

- Separate decision-makers: involve HR or a second reviewer for major actions like write-ups, demotions, or terminations

Mistake 5: Forgetting That Witnesses And Supporters Are Also Protected

Retaliation risk expands when a workplace targets the “orbit” around the complaint: witnesses, coworkers who shared information, or people who simply supported the reporter. Managers sometimes view these employees as disloyal or disruptive, especially if they participated in interviews or provided texts, emails, or context.

Treat participation as a normal business duty, like cooperating with a safety inspection. The message should be clear: cooperation is expected, and no one will be punished for it. If managers speak negatively about witnesses or begin sidelining them, the organization can end up defending multiple retaliation claims instead of one complaint.

Practical manager habits that reduce witness-related risk:

- Thank employees for cooperating without asking what they said

- Do not speculate about credibility or motives

- Keep assignments and opportunities consistent during the process

- Flag any team backlash early so HR can address it

Training That Closes The Gap Between Policy And Behavior

Many workplaces have anti-retaliation language in a handbook, but managers still trip over everyday decisions because they have not rehearsed the gray areas. Training works best when it includes realistic scenarios: scheduling changes, performance coaching timing, witness participation, and the difference between separation and punishment.

If you are already running New York sexual harassment prevention training, build a short manager segment that focuses on retaliation triggers and the “two sets of eyes” review process for job actions after a complaint. Managers should leave with phrases they can use, actions they should pause on, and a clear pathway to HR before they make changes.

Multi-State Pitfalls: Consistency Beats Guesswork

Managers who oversee teams across states sometimes assume the same informal practices will be fine everywhere. A casual “we’ll just move you to another shift” decision might be treated differently depending on local expectations, and inconsistency across locations can damage credibility during an investigation.

If your organization also provides sexual harassment training in NYC, use that as a reminder to standardize your anti-retaliation playbook across locations: consistent documentation practices, consistent review checkpoints, and consistent language from managers. Consistency makes it easier to defend decisions because it shows the organization reacts the same way, regardless of who complained.

Mistake 6: Mishandling Leave, Remote Work, And Flex Requests After A Report

After a complaint, employees sometimes request time off, a remote arrangement, or schedule flexibility because the workplace feels stressful. Managers can accidentally create retaliation exposure by denying requests more harshly than they would have before the complaint, or by making comments that frame the request as a consequence of reporting.

Keep the conversation grounded in normal business criteria. If flexibility is not available, explain why in practical terms and offer alternatives that do not feel punitive. If flexibility is available, apply the same standard you would use for any employee, then document the reasoning.

Two habits matter here:

- Stick to role-based rules: what the job requires and what the team can support

- Stick to respectful language: no blaming the employee for “creating” the need

Mistake 7: Weak Documentation That Leaves A Blank Space For Assumptions

When documentation is thin, people fill the gaps with stories. In a retaliation dispute, that story often becomes: “The complaint happened, and then everything changed.” Managers can protect the organization by documenting neutral business reasons, timing, and the alternatives considered.

Documentation does not have to be long. It has to be clear, dated, and tied to objective factors. A short note that explains why a schedule change was made, what options were offered, and who approved it can make the difference between a clean record and a suspicious timeline.

A simple documentation checklist for post-complaint decisions:

- Date the issue arose and date the decision was made

- Objective reason for the action, stated without emotion

- Alternatives considered and why they were not chosen

- Who reviewed or approved the decision

- Plan to revisit any temporary changes

A Retaliation-Safe Manager Playbook That Works Under Pressure

The best managers treat post-complaint decision-making like handling evidence with gloves. You can still lead, coach, and run the operation, but you slow down on actions that affect someone’s job and you bring in a second reviewer when stakes are high.

Start with a short routine that becomes automatic. When a complaint, report, or witness participation occurs, the manager should pause before making changes and use the same steps every time. That pattern is protective because it is predictable and fair.

Use this quick playbook:

- Pause on major actions: discipline, demotion, schedule cuts, termination

- Call HR early: explain the business need and the proposed action

- Compare to peers: would we do this if no complaint existed?

- Offer choices when possible: avoid forcing a harmful change

- Document the “why” in plain language

What To Do If Retaliation May Have Already Happened

Sometimes a manager realizes, too late, that a decision could look retaliatory. The right move is not to double down. The right move is to stabilize, review, and repair. A quick correction can reduce harm, even if it cannot erase the misstep.

Start by gathering the timeline: what occurred, what actions followed, and who made decisions. Then consider whether a remedy is possible, such as restoring hours, returning a project, correcting a written record, or offering a neutral alternative. Address team behavior as well, because social retaliation can keep harming the employee even after a formal fix.

Two practical next steps help:

- Ask HR for a structured review of decisions made after the protected activity

- Reset expectations with the team around professionalism and non-retaliation

Closing: Lead So Reporting Feels Safe, Not Risky

A workplace report should be a signal that the system is working, not a trigger that punishes the person who spoke up. Managers create liability when they treat the complaint as a disruption to manage, instead of a process to respect. Small moves, made quickly, can land hard.

If you manage people in New York, take retaliation prevention personally in the best way: slow down, ask for a second set of eyes, and document your reasoning like you expect someone else to read it later. When managers model calm, fair leadership after a complaint, they protect the employee, the team, and the organization.

FAQ

What Actions Most Often Violate Anti-Retaliation Rules In New York?

The most common problems involve sudden changes that affect someone’s work life after they report or participate in an investigation. Cuts in hours, undesirable shift changes, removing key duties, or starting discipline that was not present before are frequent triggers. Social pressure can count too. Isolation, cold treatment, or allowing coworkers to label someone as “a problem” can become part of a retaliation claim.

Can A Manager Discipline An Employee After A Complaint Without Creating Risk?

Yes, but the discipline should be consistent with pre-complaint standards and tied to clear, objective performance or conduct issues. A good test is whether you would have taken the same step if no complaint existed. Bring HR into the decision, keep the language neutral, and document the reason, timing, and any coaching that happened before the protected activity.

Does Retaliation Only Apply To The Person Who Filed The Complaint?

No. Anti-retaliation protections can extend to employees who act as witnesses, share information, or support a coworker in the process. If a manager punishes someone for cooperating, that can create a separate retaliation issue. Treat participation like a normal workplace duty. Keep assignments, opportunities, and tone consistent for everyone involved.

What Should Managers Say To The Team While An Investigation Is Ongoing?

Managers should set expectations about professionalism without discussing details of the report. A simple message works best: respect coworkers, avoid gossip, and keep communication work-related. If the team is tense, focus on behavior standards rather than motives or outcomes. That protects confidentiality and reduces the risk of social retaliation.

How Can Employers Prove They Followed Anti-Retaliation Rules In New York?

Clear timelines and neutral documentation help: why a decision was made, what alternatives were considered, and who reviewed it. Consistent treatment across employees matters as well, especially for scheduling, performance management, and access to opportunities. A repeatable review step, where HR or a second leader checks major job actions after protected activity, can prevent avoidable mistakes.