The first time an employee told me she wanted to file a complaint, she came into my office with a crumpled sticky note.

On it were a date, a short quote, and the name of a manager. She turned it over in her hands and said, “If I say this out loud, everything changes, right?”

That mix of fear and relief is common. People see comments, messages, or behavior that cross a line, but speaking up feels risky. What if no one believes you? What if the person is well connected? What if reporting hurts your career more than the behavior itself?

You should not have to carry that tension alone. Learning how to report inappropriate workplace behavior safely and confidentially gives you more control. It offers a clear next step, instead of leaving you stuck between anger and silence.

This guide is written for employees, supervisors, and HR professionals who want something practical, human, and grounded in real workplace dynamics.

Why Speaking Up About Misconduct Feels So Heavy

If you keep hesitating, there is usually a reason. Most people are not “too sensitive.” They are reading the room.

Common worries include:

- Being labeled dramatic, emotional, or difficult

- Subtle payback, like fewer projects or changed schedules

- Losing friendships or support on the team

- Not being believed if the person has power or popularity

- Getting lost in policy and legal jargon

You might also remember other jobs where someone reported a problem and “mysteriously” left a few months later. That memory does not disappear just because a policy says “no retaliation.”

Naming these fears does not fix everything, but it can remind you that your hesitation is rational. The goal is to give you tools so that, if you choose to report, you feel prepared rather than alone.

How To Report Inappropriate Workplace Behavior Safely And Confidentially

Reporting feels less overwhelming when you break it into smaller steps. You can move at your own pace instead of treating it like one giant leap.

Start a private log in plain language

Use a notebook, secure personal document, or app that is not shared at work. Write down dates, times, locations, who was present, and what was said or done. Keep it concrete: “May 3, 10:15 a.m., conference room, Supervisor X said Y in front of A and B.”

Save what you already have

Hold onto emails, chat messages, calendar invites, screenshots, or photos that show what happened. Do not record people or dig into systems in ways that violate law or company policy. Focus on evidence that is naturally in your hands.

Revisit your handbook and policies

Most organizations explain how to report in their code of conduct, harassment policy, or employee handbook. You might find this on the intranet, in onboarding materials, or in a policy folder from HR. Look for who to contact, what counts as misconduct, and what process they follow.

Choose a reporting path that feels realistic for you

Common options:

- HR or People team

- A trusted manager who is not involved

- Compliance, legal, or ethics office

- Anonymous hotline or online portal

If your manager is the person involved, you can skip them and go higher or sideways in the structure.

Write a clear, focused report

Use your notes to describe:

- What happened

- When and where it happened

- Who was involved or present

You can share how it affected you, but try to keep the story specific instead of only emotional. Concrete details help whoever receives your report know what to check.

Ask about confidentiality and next steps

You are allowed to ask:

- Who will see my name?

- How will my report be stored?

- What usually happens after someone reports?

Having a rough picture of the process can keep you from filling in the gaps with the worst possible story.

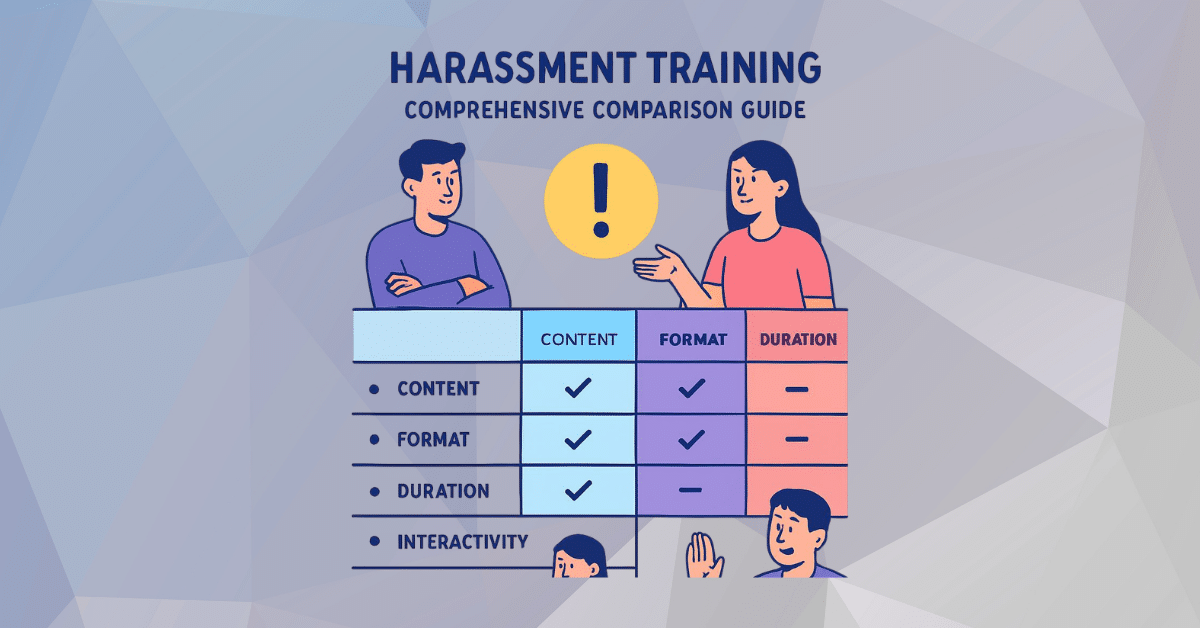

How To Tell When Behavior Has Crossed The Line

One of the biggest doubts people carry is, “Maybe this is just how work is” or “Maybe I am overreacting.” Misconduct is often not a single explosive event. It is a pattern.

Warning signs:

- Repeated jokes or remarks about appearance, identity, or personal life

- Offensive memes or images in work chats or emails

- Yelling, insults, or threats in front of others

- Excluding someone from meetings or information as payback

- Unwanted physical contact, hovering, or standing too close on purpose

- Pressure to “just let it go” when you raise a concern

Gender-based misconduct in the workplace could look like comments about someone being “too emotional for leadership,” mocking how a coworker dresses, brushing off nonbinary pronouns, or quietly steering promotions toward one gender. Each single moment might be brushed off as “not a big deal,” but the combined effect is heavy.

If you are changing your routes through the office, muting specific chats, or feeling your stomach drop when a certain person walks by, your body may be telling a story your mind is still trying to rationalize.

Confidential And Anonymous Reporting Options

Most modern reporting systems use more than one channel so people can choose what fits their situation.

You might see:

- A general HR or employee relations email

- A named contact for ethics or compliance

- An external whistleblower phone line

- A secure online platform with case tracking

- Union or worker representative contacts

- An independent ombudsperson

Confidential reporting means your identity is known to a small group that has a job-related reason to handle the situation, but your name is not shared widely. Anonymous reporting means your name is not attached at all.

Anonymous options are especially helpful when:

- The person you are reporting has a lot of power

- You fear intense backlash

- You want to flag something early and are not ready to attach your name

The tradeoff is that investigators might not be able to ask follow up questions easily. Some systems allow you to log in with a code and answer questions while staying anonymous, which can be a middle path.

If you feel safe enough, confidential reporting with your name often gives the organization more room to act. But any signal that highlights risk or harm can help.

What Usually Happens After You Report

After you send your report, you might feel like it disappears into a black box. Knowing the typical steps can make that waiting period a bit more bearable.

Intake and initial review

A designated person or team logs your report, checks the details, and decides who needs to handle it. They might reach out to you for a quick clarification.

Short term safety measures

If needed, the company may adjust schedules, move people to different projects, change seating, or place temporary restrictions on contact while they gather information.

Investigation

This stage often includes:

- Interviews with you and the person you reported

- Conversations with witnesses

- Review of emails, chat logs, schedules, or security footage, where available

- Investigators compare what they find to policy language and relevant law.

Leaders decide whether policies were broken and what should happen as a result. Outcomes can range from coaching or training to formal discipline or termination. Sometimes, team processes or training are updated simultaneously.

Feedback to you

Because of privacy obligations, you might only hear phrases like “We confirmed a policy issue” or “Appropriate action was taken.” That can feel vague, especially if you were hoping for a play-by-play, but it does not always mean nothing changed.

If you honestly feel your report was ignored or you are treated worse afterward, it may be time to raise that concern again or explore outside options.

Protecting Yourself From Retaliation

Retaliation is any negative change that is linked to your decision to report, not just being fired.

Examples:

- Suddenly poor performance reviews that do not match your actual work

- Loss of key projects or clients without clear explanation

- Shift changes that create hardship

- Gossip, cold behavior, or jokes about you “causing trouble”

- Pressure to withdraw your complaint

Most laws that cover harassment and discrimination also protect employees from retaliation. Internal policies often have a section that spells this out plainly.

To protect yourself:

- Keep writing things down after your report, especially changes in your workload, feedback, or relationships

- Save emails or messages that mention your complaint or react to it angrily

- Speak up quickly if something feels like retaliation, using the same channel or a higher one

- If internal routes lead nowhere, consider speaking with an attorney, advocacy organization, or government agency

You followed the process the company created. You should not be punished for using it.

How Leaders And HR Can Make Reporting Safer

If you are a manager or HR professional, you may be the first person someone trusts with their story. How you handle that first conversation matters.

Supportive responses often include:

- Letting the person finish before jumping in with questions

- Thanking them for speaking up, even if what you hear is uncomfortable

- Avoiding promises you cannot keep, like specific outcomes or timelines

- Explaining your responsibilities: what you must share, with whom, and why

- Checking in later, even if you do not have many details to share

Day to day, leaders can:

- Talk openly about respect and behavior in regular meetings

- Interrupt harmful jokes or comments in real time

- Be honest about their own mistakes and show how they repair them

- Support employees who step up as bystanders, not just direct reporters

People notice whether leaders protect only their peers and favorites or truly apply the same standard to everyone.

Legal And Policy Basics For Employees

Every location has its own rules, but a few themes often repeat:

- Laws that protect people from discrimination and harassment tied to things like race, sex, disability, age, and religion

- Employer responsibilities to prevent and respond to harassment and violence

- Whistleblower protections for those who report illegal activity or safety problems

- Special duties for supervisors when they learn about possible misconduct

Your company policies usually go beyond minimum legal rules and cover bullying, conflicts of interest, digital conduct, and general professionalism. If someone breaks those standards, the organization can act even without a lawsuit.

If you are unsure what applies to you, you can ask HR to walk through the pieces that relate to your role, site, or state.

How Training Helps People Speak Up Earlier

Good training changes the way people talk about hard topics. It gives shared language and a shared sense of “This is how we treat each other here.”

For instance, a company using a sexual harassment in california training course can move beyond slides full of legal citations. They can show chat examples, replay awkward but realistic scenarios, and ask managers to practice how they would respond if an employee said, “I am not comfortable around this person.” That kind of practice sticks.

Stronger training programs tend to:

- Use real situations people recognize from their work life

- Explain reporting options in plain, everyday language

- Clarify that managers must act when they receive a complaint

- Emphasize that retaliation is itself a violation

- Invite questions instead of rushing through the session

When training and behavior line up, people feel less alone when something goes wrong. They know where to go, what to say, and what the organization claims it will do.